David Sedaris is no clown

The author offers his take on writing, success, family

- plus Peruvian skulls, Athenian

graffiti and Amtrak adventures

Engulfed in Flames by David Sedaris

"IT'S really hard to get any respect if you are a humour writer," David Sedaris explains. His last visit to Greece, the country of his IBM-engineer retiree father, was on a family trip 25 years ago. Today, with five side-splitting short story/essay best-sellers and regular articles in the New Yorker, Sedaris certainly has respect.

But even though one of the three stories he read at the Hellenic American Union on April 7 was about a turd he once encountered in the toilet at a dinner party, Sedaris is no clown.

Success has its dangers, the 51-year-old with a naughty twinkle in his eye and Woody Allen-esque intonation explains to the Athens News the morning of the reading.

"All I wanted was to write for the New Yorker and to have a book," he says. "But then there comes a point when you are offered more, right?" Sedaris notes.

Turning down David Letterman's offer to appear regularly on his show, covering events like the Republican National Convention, was part of his decision to remain a writer rather than become a personality, "corroding all the respect".

Sedaris became known for his tales of alternately touching, hilarious and surreal autobiographical suburban adventures - often featuring himself and family members - with his first books Barrel Fever (1994) and Naked (1997). In person, he has the same chatty, confidante quality as his writing style. But he also seems pretty organised and focused.

He travels with notebooks and diaries, recording lots of details. In Athens, he fits a neat stack of index cards with all the Greek words he knows into a single shirt pocket. At the Hellenic American Union reading, he shares his favourite word with the crowd, revealing his penchant for the grotesque. "Splinandero!" (a dish of sheep's intestines with spleen), he announces, grinning like a spelling bee contest winner.

The Sedaris file

Sedaris may have started out an alienated gay kid in a quirky North Carolina family, but he has become international in more ways than one. With his books being translated into other languages, he's become careful about using pop cultural references of The Brady Bunch TV show variety.

He and partner Hugh (also featured in the stories) moved to France a decade ago, and Sedaris now splits his time between there and London. The author is prone to saying, "I lived in the United States for 40 years. That was enough."

He admits to several recent departures in his personal life from what he's previously written about himself. For one, he works on a computer, though he once swore allegiance to his typewriter. He also quit smoking, despite writing about that fetish (and a deep appreciation for drugs) for years. But cell phones and email are not yet a part of Sedaris' world.

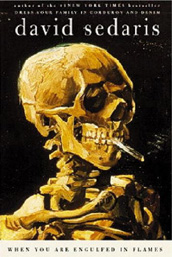

He writes constantly, with many things on the burner at once. Two weeks ago he turned in the final draft of his upcoming book When You Are Engulfed in Flames, only to immediately start working on a new book ("of fables"), a New Yorker piece and a speech for a US bookstore annual meeting.

Writing is never a chore for him. "I've been pretty lucky that way," he reflects. "I can't think of a time when writing felt like a job to me and I thought, 'Goddamit, I have to do this.'"

Spoken words

different voices and tones to read three short

stories

The audience roared as David Sedaris assumed different voices and tones to read three short stories

In Athens, Sedaris got big laughs for his reading of "Jesus Saves" (about his French class using a limited vocabulary to explain what Easter is), "Nuit of the Living Dead" (where Sedaris spooks tourists and drowns a mouse) and scatological "Big Boy". Though it is probably the umpteenth time he's read them, he seems to enjoy it. (It seemed a poor decision, however, to have the entire Greek translation read after each one.)

The author, some of whose works have come out on audio tapes too, explains of readings: "It's the laziest form of show business there is, so it's perfect for me. Because I don't want to memorise anything. I don't want to have eye contact. I hate it when you go to a theatre and the actor on stage is going to look you in the face. It's like 'Oh, please, don't look me in the face.'"

Sedaris first received nationwide exposure on the US' National Public Radio after radio host Ira Glass discovered him reading at a Chicago bar. Though he still appears on the radio "for Ira", he prefers visible audiences. "When you read for the radio, you have an engineer who is listening, but that is really your only audience," he notes.

It's really about the journey, not the destination when he's writing. Sedaris explains: "When you are writing about your life, the question is: 'Where do you start it and where do you end it? ...Lately, I've been writing these stories, like 'Oh I'm going to talk about this for a while, and now I'm going to talk about this, and just going to see where it winds up.' Like this story that I'm working about this train ride."

Coming soon to a magazine or a bookshelf near you: the tale of Sedaris and a traveller (name changed to protect the not-so-innocent) hijacking an Amtrak train's ladies' lounge in order to smoke pot, circa 1990. Though he admits to being embarrassed about his part in that story today, Sedaris notes: "I always wanted to write about this guy that I met on the train. Nothing in his life sounded normal to me. His mother was a pot dealer, neither of his parents ever cooked, they just had pizza or take out food for dinner and then his parents got a divorce …"

In the work-in-progress, Sedaris hopes to link that trip with a train journey through Italy in 1982. "Someone always told me," Sedaris adds, "that if you're not surprised, the reader won't be. I don't know if that's true or not, but it sounded good."

Making them listen

Sedaris' pen has a broad reach, even in a single book. In Holidays on Ice, there is the classic story of Sedaris-as-a-Macy's-elf, the tale of his sister rescuing prostitute Dinah on Christmas and the morbid account of a couple hacking off their own body parts to outdo some philanthropic neighbours.

Sometimes in the earlier drafts, he's out to prove to himself that he can "get a laugh". Then he ventures into darker waters, wondering, "What would it be like to be a little deeper and to be a little bit more honest or a little bit more vivid?"

Sedaris plays a game with his readers. It's called: "Made you listen!" He applies that phrase to a story he's developing about a "man with a teenager's head in a bag" he met in London. Here's the rub: we're talking about a Peruvian relic in a taxidermist shop. But it's all about how you present it, Sedaris says, delighted with how unique his perspective is. "Most people would just say it was a 600-year-old head from Peru. But when I saw it, I didn't think 'that's a Peruvian artefact'. I thought 'that's a teenager's head in a bag'." He laughs at his devilishness.

Saving family's face

Though his family is often the butt of jokes in his books, Sedaris explains that they have a say. "When I write something about someone in my family, I give it to them first, and say, 'Is there something you'd like to change? Is there anything you want me to get rid of?'"

He also points out that there's a difference between himself, partner Hugh, his family and their literary personas. This doesn't mean that fans understand the difference. Once a drunk man called up his brother (aka "The Rooster") at 2am.

Sedaris says he can't always make people see what he does. He explains: "Writing gives you the illusion of control. Like you think, 'OK, I can make people understand that my sister is really unique and funny. I can make the world understand that.' And then the story comes out and people say, 'How's your neurotic sister?' And it's like, 'Neurotic? I just thought she was funny.'"

He pulled out of having a film version done of his book Me Talk Pretty One Day due to his family's concerns. But he's considering a proposal by Juno director Jason Reitman to make a film out of a different work. "I liked Juno, and I liked Thank You for Smoking, so I thought, oh, OK. And it doesn't involve my family. I thought, well, maybe I'll do that."

When asked if his stories are true, Sedaris replies, "I exaggerate." Some people, however, cannot take a joke. Fact-checkers are a thorn in his side. He explains: "The New Yorker fact-checking department, is MUR-DER. MUR-DER." Those meticulous folk wouldn't accept Sedaris' Normandy spiders "so obese that their legs were rubbing together" or his North Carolina wolf spiders "the size of a baby's hand". He had to explain "it's a JOKE".

More annoying was the nit-picking of a writer who took his book Naked and tried to check if Sedaris really did take guitar lessons from midgets or hitch-hiked with a quadriplegic. He says, "There is a really long history of hyperbole in American humour writing, and I see no reason to break it."

As Sedaris heads off to Italy with the third Greek translation of one of his books (Naked), it's tempting to wonder what will end up in a future book from his short Greece trip. Will it be the verbal assaults? ("You just make a little mistake and someone yells at you.") The graffiti? ("There must be something around the Parthenon. But if there wasn't, I mean how long would it take for it to be completely covered?") Or some teeny detail of Athens life everyone else has missed tucked away in one of his notebooks?